C

G

I

L

L

M

A

T

H

E

M

A

T

I

C

S

M

C

G

I

L

L

M

A

T

H

E

M

A

T

I

C

S

M

C

G

I

L

L

M

A

T

H

E

M

A

T

I

C

S

M

C

G

I

L

L

M

A

T

H

E

M

A

T

I

C

S

M

C

G

I

L

L

M

A

T

H

E

M

A

T

I

C

S

M

C

G

I

L

L

M

A

T

H

E

M

A

T

I

C

S

M

C

G

I

L

L

M

A

T

H

E

M

A

T

I

C

S

M

C

G

I

L

L

M

A

T

H

E

M

A

T

I

C

S

M

C

G

I

L

L

M

A

T

H

E

M

A

T

I

C

S

M

C

G

I

L

L

M

A

T

H

E

M

A

T

I

C

S

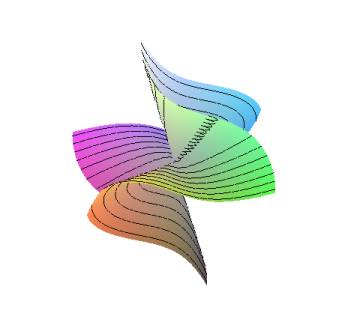

Algebraic geometry is one of the oldest and vastest branches of mathematics.

Besides being an active field of research for many centuries, it plays

a central role in

number

theory, differential geometry, group theory, mathematical physics and

other branches of science.

![]()

Initially, algebraic geometry was concerned with the study of curves in the plane and really started boosting up with the discovery of projective geometry. In this geometry, the line k (k any field) is completed by adding one point at infinity resulting in the projective line P1, the plane k2 is completed by adding a projective line at infinity to yield the projective plane P2. Thus P2= k2U P1=k2 U k U{pt}.

On a more conceptual level, the projective space Pn over a field k is the parameter space of lines in kn+1. Such a line is determined by a non-zero point on it (a0, ... , an), where one is allowed to replace (a0, ... , an) by (ta0, ... , tan) for any non -zero t in k. We denote such a class of points by (a0: ... : an). Thus Pn is the collection of (a0: ... : an). The points with a1 not equal to 0 may be normalized so that a1 = 1. Then a1, ... , anin (1: a1: ... : an) are determined uniquely and are in one to one correspondence with kn by the map (1: a1: ... : an) ---> (a1, ... , an). The complement is the points (0: a1: ... : an), which are precisely Pn -1 . Thus we get an inductive dissection Pn = kn U kn-1 U ... U k U {*}, where * is the point (0: ... :0:1).

One of the nicest theorems is

Bezout's theorem: Two curves C and D in P2, defined by equations of degree M and N intersect at MN points, counting multiplicity.

For long time geometry was the study of projective geometry. By that one means the study of sets defined as the set of solutions for a given system of homogeneous polynomials. Such sets look like a set Y in kn such that the points of Y are the common solutions to a system of polynomials (f1, ... , fr) in n variables, and where one adds to Y its limit points at infinity.

Another problem was to find a way of actually saying what is geometry. One can think about geometry as a collection of objects, where for any two objects it is known whether "one lies on the other", and where it is known what is a regular function on such a structure.

Yet another problem is putting on a firm ground the "feeling" that a family of algebraic sets (say a family of curves) varying smoothly in time is "like" a curve defined using equations with integer coefficients where for every prime number one can consider the curve modulo this prime. Hence the curve varies over the parameter space whose points are primes.

Members of the department

studying algebraic geometry are Peter

Russell and Eyal Goren.

Members whose interests are bordering with algebraic geometry are Niky

Kamran, Jacques Hurtubise, Henri

Darmon and many of the members of CICMA.

![]()

Eyal

Goren: I am interested in questions where number

theory is studied via geometry. Specific

key words are modular forms, moduli spaces, elliptic curves, abelian varieties,

p-divisible groups, L functions.

In the last couple of years I was working on the ambitious project of bringing our knowledge of moduli spaces of abelian varieties and modular forms on them to the level of our knowledge in the case of elliptic curves. Here we comment that an abelian variety is a complete algebraic group (over C it is topologically a torus) and the moduli space is a variety that parameterize all those abelian varieties. Every variety gives a point in the space and a curve C in the moduli space gives a family of abelian varieties parameterized by C.

In the case of elliptic curves this theory played a crucial role in the proof of Fermat's last theorem. It is therefore expected that much deep mathematics is to be discovered in the study of such moduli spaces, connecting questions from number theory (in particular Diophantine equations and modular forms) to questions on the geometry of these moduli spaces.

Peter Russell: I have long been interested in studying affine spaces and closely related varieties (e.g., over C, contractible affine varieties) as algebraic varieties in their own right. The famous cancellation problem, for instance, asks whether X is an affine space provided that X x C is an affine space. This is known if the dimension of X is at most 2.

Closely related is the quest to understand the automorphism group of affine space Cn, still a mystery for n bigger than 2. A quite recent result (obtained in collaboration with M. Koras and others) says that C* actions on C3 are linear in a suitable coordinate system. Again, this is not known for Cn, n >3.

Among my other interests

are the study of embeddings of rational curves in the affine plane (generically

rational curves, closed embeddings of C*, ...); some special topics

in positive characteristic geometry (purely inseparable forms, Frobenius

sandwiches, ...).

![]()

Courses (current and recent years):

1997-1998:

Commutative algebra and algebraic geometry (Algebre 1). UdM.

MAT 6608. Lecturer: B. Broer. Automn 97.

Topics in Algebra III: Approaches to the Jacobian Problem. McGill.

189-722A. Lecturer: A. Sathaye.

1998-1999:

Algebraic surfaces. McGill University. 189-725A. Lecturer: P.

Russell. (A semester course leading to the study of systems of curves on

an algebraic surface and the notion of Kodaira dimension for compact and

non-compact surfaces).

Algebraic Curves. McGill. 189-612B. Lecturer:J. Hurtubise.

1999-2000:

Topics in Geometry and Topology. McGill University. 189-706A/707B.

Lecturer: E. Goren. (A year long course in algebraic

geometry, from classical theory to schemes. The course is aimed

at the graduate, or advanced undergraduate level. Pre-requisites

are some basic algebra and topology. For more details go

here.

)

2000-2001:

Introduction to Riemannian symmetric spaces. (Topics in Geometry

and Topology I). McGill 189-706A, MW 10:30 - 12:00, Room 1214. Lecturer:

F. Andreatta. The course is aimed at the beginning graduate student

level and higher, and is open to advanced undergraduate students. After

introduction of the necessary background in differential geometry and Lie

theory, the focus would be the notion of symmetric spaces, their properties,

their relation and classification in terms of Lie groups due to Cartan.

Applications and connections to number theory and arithmetic algebrai geometry

(e.g. classification of variations of Hodge structures, Shimura varieties)

would be given in detail depending on time.

Elliptic Curves (Topics in Algebra). Concordia MAST 699I/4.

Lecturer: Chantal David. This course will cover the basic theory of elliptic

curves and algebraic curves. The recommended textbook is: The arithmentic

of elliptic curvesby J. Silverman. The prerequisites for this course are

part of the standard background in abstract algebra (groups, rings, field

extensions etc). A

first course in algebraic number theory is also recommended. The course

is open to all graduate students, either at the master or the Ph.D. level.

COMING YEAR (2001-02):

Introduction to Algebraic Geometry. Lecturer: E. Goren.

This is an introductory course in Algebraic Geometry. It develops from

scratch the theory of algebraic varieties over algebraically closed fields,

including morphisms, sheaves and cohomology. The course presupposes basic

commutative algebra. The topics to be studied are: affine and projective

algebraic

varieties; regular functions and morphisms; singularities, normalization

and blow-up; sheaves, Cech cohomology and the

Riemann-Roch theorem for curves. The examples of curves, and Grassmannian

manifolds are studied in detail.

Vecotr bundles on Curves. Lecturer: E. Goren. This is a

special graduate course given within the Theme Year on Groups and Geometry

taking place at the CRM during 2001-02. The course presupposes basic algebraic

geometry at the level of the course \emph{Introduction to Algebraic Geometry}

given in the first term. It develops the theory of curves and vector bundles

of curves and their moduli. The topics to be studied are: curves, the Riemann-Roch

theorem and the Hurwitz genus formula; vector bundles on curves and their

invariants, monodromy, flat vector bundles and Weil's theorem; semi-stability;

the Hilbert scheme; geometric invariant theory; construction of moduli

spaces.

Quebec-Vermont Number Theory Seminar.

See also the activities of

Page constructed by Eyal Goren: goren@math.mcgill.ca